February 10, 2012

by Ibn Siqilli

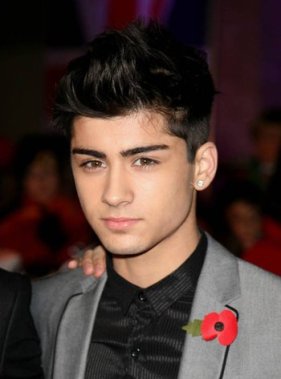

‘Ali Mahamoud Rage (‘Ali Dheere), Al-Shabab’s spokesman, at a press conference on the killing of Usama bin Laden on May 6, 2011.

‘Ali Mahamoud Rage (‘Ali Dheere), Al-Shabab’s spokesman, at a press conference on the killing of Usama bin Laden on May 6, 2011.

-Christopher Anzalone (McGill University)

UPDATE (23 February 2012): Al-Shabab’s Political and Governorates Office has issued two statements today. The first congratulates the Muslim Ummah on its formal affiliation with Al-Qa’ida Central and gives “special thanks to our amir, Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri.” It states that the Somali insurgent movement’s resources now fall under his authority. It has yet to be seen if this leads to a significant change in Al-Shabab’s Somalia-centric insurgency. The second thanks AQC’s Al-Sahab Media Foundation for producing the video announcing the affiliation as well as the Global Islamic Media Front for its longtime online distribution support of Al-Shabab.

UPDATE (17 February 2012): See insurgent photographs from a rally in Baidoa HERE.

UPDATE (14 February 2012): See a second set of insurgent photographs of the rallies HERE.

UPDATE (13 February 2012): Al-Shabab leaders have hosted celebrations across Lower Shabelle for the formalization of affiliation between their movement and Al-Qa’ida Central. Among those leaders present were spokesman ‘Ali Mahamoud Rage (‘Ali Dheere), governor of Banaadir Muhammad Abu ‘Abd al-Rahman, governor of Lower Shabelle Muhammad Abu ‘Abdullah, and preacher ‘Abd al-Qadir Mu’min. Noticeably absent, at least in insurgent photographs and the official statement announcing the celebrations, were Mukhtar “Abu Mansur” Robow and Hasan Dahir Aweys. This may or may not mean the latter two were not present. If they were not present it may be a sign of a rift, though the nature of cleavages in the movement remain hotly debated. It is not the first time that not all the “public faces” of Al-Shabab were not present at a major event. For example, ‘Ali Rage was not pictured in insurgent photographs or video footage of the movement’s conference marking the killing of Usama bin Laden in May 2011. Signs and banners held by civilians present express “joy” at the “union of the mujahideen” and “jihadi movement.” To see insurgent photographs and read the official statement, see my post at VIEWS FROM THE OCCIDENT.

In a new media release, half audio message and half video message, released on Thursday, February 9 by Al-Qa’ida Central’s (AQC) media outlet, the Al-Sahab (The Clouds) Media Foundation, the group’s amir, Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri, and Ahmed Godane, the amir of the Somali insurgent movement Harakat al-Shabab al-Mujahideen (Movement of the Warrior-Youth; Al-Shabaab) formally announced the official affiliation of Al-Shabab with AQC. The announcement, which was teased a day prior to its release on jihadi-takfiri Internet forums, formalizes the relationship between the two groups following a lengthy history of ideological affinity and cooperation between them. Its release has renewed discussions about how Al-Shabab should be classified, as mostly a local or regional insurgency, a transnational militant movement akin to AQC, or a mix of the two. This post, like much of my current research and writing on Al-Shabab, attempts to make a modest contribution to this discussion. I have and continue to argue that Al-Shabab is most accurately seen as a type of “glocal” militant movement, a mainly localized militant movement that uses transnational rhetoric and maintains an operational capability to carry out attacks outside of its home base inside Somalia, primarily but not necessarily limited to regional countries in East Africa.

Entitled, Glad Tidings from the Two Shaykhs, Abu al-Zubayr and Amir Ayman al-Zawahiri, the announcement is roughly evenly divided between an audio message from Godane, who is more commonly known in jihadi circles by his nom de guerre “Mukhtar Abu al-Zubayr,” and a video segment from al-Zawahiri, who stoically gives “glad tidings to the Muslim Ummah (worldwide community), in particular to the mujahideen” regarding Al-Shabab’s joining of the Al-Qa’ida organization-led jihadi movement (al-harakat al-jihadiyya) against the alliance of Crusaders, Zionists, and their allies and agents, the munafiqeen (hypocrites, a term used for those who claim to be Muslims but whose actions prove otherwise). He welcomes “our brothers” Al-Shabab and praises the steadfastness of the movement against the mounting Crusader attacks on it by the United States, Ethiopia, and Kenya, all of whom have become increasingly involved in the Somali civil war that pits Al-Shabab against the weak but internationally-backed Transitional Federal Government (TFG), which depends on the nearly 10,000 African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) soldiers for its survival. Al-Zawahiri also urges Somalis to stay away from those religious scholars (‘ulama) who seek to lead them astray and who support the corrupt TFG leaders who have allied themselves to “Crusader” forces.

Entitled, Glad Tidings from the Two Shaykhs, Abu al-Zubayr and Amir Ayman al-Zawahiri, the announcement is roughly evenly divided between an audio message from Godane, who is more commonly known in jihadi circles by his nom de guerre “Mukhtar Abu al-Zubayr,” and a video segment from al-Zawahiri, who stoically gives “glad tidings to the Muslim Ummah (worldwide community), in particular to the mujahideen” regarding Al-Shabab’s joining of the Al-Qa’ida organization-led jihadi movement (al-harakat al-jihadiyya) against the alliance of Crusaders, Zionists, and their allies and agents, the munafiqeen (hypocrites, a term used for those who claim to be Muslims but whose actions prove otherwise). He welcomes “our brothers” Al-Shabab and praises the steadfastness of the movement against the mounting Crusader attacks on it by the United States, Ethiopia, and Kenya, all of whom have become increasingly involved in the Somali civil war that pits Al-Shabab against the weak but internationally-backed Transitional Federal Government (TFG), which depends on the nearly 10,000 African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) soldiers for its survival. Al-Zawahiri also urges Somalis to stay away from those religious scholars (‘ulama) who seek to lead them astray and who support the corrupt TFG leaders who have allied themselves to “Crusader” forces.

Al-Zawahiri sits in front of a green curtain, which appears to be felt. He has sat in frot of the same or a very similar curtain in a number of other recent video messages including Days with the Imam: Part 1, released November 15 of last year, The Glory of the East Begins with Damascus, released July 27, and And the Defeats of the Americans Continue, released October 11. The background setting of the AQC amir’s location suggests that the video segment featuring him was recorded fairly recently, within the last seven months.

Al-Zawahiri sits in front of a green curtain, which appears to be felt. He has sat in frot of the same or a very similar curtain in a number of other recent video messages including Days with the Imam: Part 1, released November 15 of last year, The Glory of the East Begins with Damascus, released July 27, and And the Defeats of the Americans Continue, released October 11. The background setting of the AQC amir’s location suggests that the video segment featuring him was recorded fairly recently, within the last seven months.

Godane, as Al-Shabab’s amir, declares his loyalty to “our amir,” the “beloved amir, the blessed/honorable shaykh,” al-Zawahiri. During his audio segment, a static background identifies Godane as the speaker and includes a still photograph from the conference in December 2010 at which Al-Shabab announced the joining to it of Hizbul Islam, the Somali Islamist insurgent group formerly headed by Hasan Dahir Aweys, who is now a senior Al-Shabab leader.

The issuing of this announcement now, during a period when both AQC and Al-Shabab are facing mounting pressures, is telling. It is unclear at the current time who initiated this formal affiliation of Al-Shabab with AQC, or whether it was mutually initiated. AQC, faced with the loss of its founder, Usama bin Laden, and a senior operational leader and ideologue, ‘Atiyyatullah al-Libi (Jamal Ibrahim Ishtaywi al-Misrati), last year is reeling from losses inflicted by U.S. drone missile strikes and is struggling to remain a relevant force. Of the two groups, it arguably has the most to gain from formalizing its relationship with Al-Shabab, which continues to control vast swaths of territory in central and southern Somalia. The insurgent movement or its allies also reportedly have made significant inroads into parts of northern Somalia, both in the autonomous region of Puntland and a contested area between Puntland and the self-declared republic of Somaliland. Despite significant military setbacks since last spring, Al-Shabab remains a potent force within the country and its military power, even if it is in decline, remains the subject of pride for the Sunni jihadi current. With the exception of Ansar al-Shari‘a, which is at the very least affiliated with AQAP, no other AQC affiliate controls any significant amount of territory. The jihadi-insurgent “golden age” in Iraq from 2003 to 2007, during which AQ in the Land of the Two Rivers, the Majlis Shura al-Mujahideen (Mujahideen Shura Council), its successor the Islamic State of Iraq, controlled villages and cities in certain regions, such as Al-Anbar, has long since ended. The control and governance of territory has long been a transnational jihadi dream and Al-Shabab’s exercise of governing authority, however basic, over large parts of southern and central Somalia is thus something that AQC leaders and transnational jihadis online have long heralded as one of the best examples of what a “jihadi state” can accomplish. Despite its delusions of grandeur with the Islamic State of Iraq, which, in terms of its actual ability to exercise significant governing authority over territory, exists mostly on paper rather than in practice, the transnational jihadi current’s attention has been shifting away from Iraq and toward other theaters, such as Somalia.

The issuing of this announcement now, during a period when both AQC and Al-Shabab are facing mounting pressures, is telling. It is unclear at the current time who initiated this formal affiliation of Al-Shabab with AQC, or whether it was mutually initiated. AQC, faced with the loss of its founder, Usama bin Laden, and a senior operational leader and ideologue, ‘Atiyyatullah al-Libi (Jamal Ibrahim Ishtaywi al-Misrati), last year is reeling from losses inflicted by U.S. drone missile strikes and is struggling to remain a relevant force. Of the two groups, it arguably has the most to gain from formalizing its relationship with Al-Shabab, which continues to control vast swaths of territory in central and southern Somalia. The insurgent movement or its allies also reportedly have made significant inroads into parts of northern Somalia, both in the autonomous region of Puntland and a contested area between Puntland and the self-declared republic of Somaliland. Despite significant military setbacks since last spring, Al-Shabab remains a potent force within the country and its military power, even if it is in decline, remains the subject of pride for the Sunni jihadi current. With the exception of Ansar al-Shari‘a, which is at the very least affiliated with AQAP, no other AQC affiliate controls any significant amount of territory. The jihadi-insurgent “golden age” in Iraq from 2003 to 2007, during which AQ in the Land of the Two Rivers, the Majlis Shura al-Mujahideen (Mujahideen Shura Council), its successor the Islamic State of Iraq, controlled villages and cities in certain regions, such as Al-Anbar, has long since ended. The control and governance of territory has long been a transnational jihadi dream and Al-Shabab’s exercise of governing authority, however basic, over large parts of southern and central Somalia is thus something that AQC leaders and transnational jihadis online have long heralded as one of the best examples of what a “jihadi state” can accomplish. Despite its delusions of grandeur with the Islamic State of Iraq, which, in terms of its actual ability to exercise significant governing authority over territory, exists mostly on paper rather than in practice, the transnational jihadi current’s attention has been shifting away from Iraq and toward other theaters, such as Somalia.

AQC leaders, from Bin Laden to al-Zawahiri to Abu Yahya al-Libi, have long held up Al-Shabab as a source of pride to the transnational jihadi current. During its heyday from roughly 2008 through the summer of 2010, Al-Shabab represented, for both AQ, broadly defined, ideologues and online jihadis one of the best examples of what can be accomplished, in terms of controlling and governing territory, by “steadfast mujahideen” with few resources in the face of a numerically and technologically-superior set of adversaries, in this case AMISOM, Ethiopia, and their U.S. backers. This was highlighted, for example, by Abu Yahya al-Libi in Al-Sahab’s 2008 “9/11 anniversary” video, The Results of Seven Years of the Crusades, and he more recently argued that the Kenyan military intervention in Somalia is a step on the way to victory for the “mujahideen” since it will lead to further economic catastrophe for Kenya and the U.S. AQAP’s deputy amir, Sa’id al-Shihri, also praised Al-Shabab in a February 2010 audio message in which he urged increased cooperation between the two groups.

AQC leaders, from Bin Laden to al-Zawahiri to Abu Yahya al-Libi, have long held up Al-Shabab as a source of pride to the transnational jihadi current. During its heyday from roughly 2008 through the summer of 2010, Al-Shabab represented, for both AQ, broadly defined, ideologues and online jihadis one of the best examples of what can be accomplished, in terms of controlling and governing territory, by “steadfast mujahideen” with few resources in the face of a numerically and technologically-superior set of adversaries, in this case AMISOM, Ethiopia, and their U.S. backers. This was highlighted, for example, by Abu Yahya al-Libi in Al-Sahab’s 2008 “9/11 anniversary” video, The Results of Seven Years of the Crusades, and he more recently argued that the Kenyan military intervention in Somalia is a step on the way to victory for the “mujahideen” since it will lead to further economic catastrophe for Kenya and the U.S. AQAP’s deputy amir, Sa’id al-Shihri, also praised Al-Shabab in a February 2010 audio message in which he urged increased cooperation between the two groups.

The fact that Al-Shabab’s successes in Somalia were only made possible by a unique set of circumstances that do not exist and are likely not reproducible in other regions seems not to have been considered by them. In other words, Al-Shabab’s success at capturing and holding territory has provided AQ and other likeminded jihadis with hope that it is possible for “mujahideen” to implement “God’s rule,” a harsh implementation of a rudimentary form of shari‘a, and act as executors of a kind of state power.

Anwar al-‘Awlaqi, the late American militant preacher affiliated with AQAP who was killed in a U.S. drone missile strike on September 30, was perhaps the most outspoken in his view that Al-Shabab represents the potential of a jihadi state. In a December 21, 2008 post on his blog, he lauded and congratulated Al-Shabab for its victories in Somalia against the Ethiopians, AMISOM, and the TFG, writing that they filled “our hearts with immense joy.” He went on to describe Al-Shabab’s project in Somalia as a “university” that “will graduate” distinguished alumni who can share their experiences with and educate other “mujahideen” in implementing a similar social and governing program in other regions. The Somali theater, he wrote, “will provide its graduates with the hands-on experience that the Ummah greatly needs for its next stage.”

Al-‘Awlaqi reiterated his positive assessment of Al-Shabab in his first, and thus far only publicly released, interview with AQAP’s Al-Malahem Media Foundation, which was released in May 2010. When asked to clarify his position on the Somali insurgent movement, he said, “The various Islamic movements are searching for a solution for the Ummah, as are the scholars…Today we are seeing the solution in front of our very eyes in Somalia. This small hand of mujahideen, with limited resources, has been able to establish a state and rule with God’s almighty Shari‘a. Today, they are providing solutions for the people…Today, they are dealing with the realities and providing solutions from the Islamic Shari ‘a. For this reason, as I mentioned, this is a unique experience from which the Ummah must derive benefit.” Clearly, this is a heavily selective description of Al-Shabab’s execution of governing authority over wide swaths of Somalia. However, al-‘Awlaqi’s response clearly shows how important the Somali theater has been to jihadis as a model to emulate.

SEE HERE FOR A VIDEO CLIP OF ANWAR AL-‘AWLAQI’S DESCRIPTION OF AL-SHABAB.

Despite Al-Shabab’s importance in illustrating how a jihadi state can be run in praxis, the movement’s leaders have not been as frequently cited in videos produced by AQC and its affiliates as the reverse. An audio clip of Godane was used in Ghazwat al-Mansura, a video in AQIM’s series The Shade of Swords, released on July 22, 2010, to my knowledge for the first, and so far only, time.

For its part, Al-Shabab has for a long time closely affiliated itself ideologically with AQC and the transnational jihadi current in the hope of garnering benefits from this relationship that would otherwise not be available to it. This has been particularly true in terms of the movement winning financial support and potentially new recruits from outside of Somalia, particularly when the number of diaspora recruits from North America and Western Europe began to slow following the Ethiopian military withdrawal in January 2008.

Mukhtar Robow

Mukhtar Robow

Al-Shabab from its early stages embraced and has been strongly influenced by the charismatic persona of Bin Laden. His image and clips of his audio and video messages have been used in the insurgent movement’s video productions since at least 2008. For example, his image and audio clips of him were used prominently in Al-Shabab’s video series Martyrdom Operations in Somalia. Insurgent leaders, from Godane to Mukhtar “Abu Mansur” Robow, ‘Ali Mahamoud Rage (‘Ali Dheere), and Hasan Dahir Aweys have continuously spoken with great affinity for Bin Laden and the late AQC founder continues to occupy a place of prominence in Al-Shabab’s media productions. The insurgent movement held a major conference entitled “We Are all Usama” in mid-May following his killing in Pakistan. Senior Al-Shabab leaders including Aweys, Robow, Fu’ad Muhammad Khalaf “Shongole,” and its governor of the Banaadir region, Abu ‘Abd al-Rahman, and ‘Abd al-Qadir Mu’min were present, as was American member Omar “Abu Mansur al-Amriki” Hammami.

Hasan Dahir Aweys

Hasan Dahir Aweys

The clearest example of Al-Shabab’s ideological affinity for Bin Laden is a 48-minute video entitled Labbayk Ya Usama, which translates approximately to, “We Heed Your Call” or “At Your Service,” released on September 20, 2009 by Al-Shabab’s media wing. In the video, Godane refers to Bin Laden, whom he calls by his kunya Abu ‘Abdullah, as “shaykh-i-na wa amir-i-na” (our shaykh and our amir). Godane and other Al-Shabab leaders, such as Robow, Rage, and Aweys, have long described Bin Laden as the epitome of Muslim resistance to Western imperialism, epitomized by the United States, and its local clients such as Somalia’s TFG.

Insurgent ideological affinity for the transnational jihadism represented by AQC has not been limited to the personage of Bin Laden. Al-Shabab’s media apparatus, originally called simply “Media Department” and now the “Al-Kata’ib (The Brigades) Media Foundation,” has also made frequent use of video and audio clips from other prominent transnational jihadi ideologues including Al-Qa’ida Central’s Abu Yahya al-Libi (a clip of whom appears in an early Al-Shabab media production, the July 2008 Al-Shabab video eulogy for its founder, Adan Hashi Farah ‘Ayro), the late Al-Qa’ida Central commander in Afghanistan Mustafa Abu’l Yazid, and Al-Qa’ida in Iraq/Islamic State of Iraq leaders Abu Mus‘ab al-Zarqawi (after which it named a research institute that published one issue of its Internet magazine Millat Ibrahim), Abu ‘Umar al-Baghdadi, and Abu Hamza al-Muhajir. Materials studied by Al-Shabab fighters and missionaries, at academies named after ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam, include, in addition to classical and medieval books on Arabic grammar, Qur’anic commentaries, books of hadith, and prophetic biography, books by Ayman al-Zawahiri (al-Wala’ wa’l Bara’) and Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi (Millat Ibrahim).

In addition to the significant ideological affinity that Al-Shabab’s leaders have for Bin Laden and other transnational jihadi ideologues, the former also get strategic benefit from their affiliation with Al-Qa’ida and the transnational jihadi community it represents. By distributing its media materials on major jihadi Internet forums through the Global Islamic Media Front and embracing Bin Laden and other jihadi leaders, Al-Shabab is able to reach a broader audience of potential and actual supporters than it would otherwise be able to. In tandem with its recruitment networks in East Africa, Europe, Australia, and North America, this has enabled it to win new supporters, some of whom have traveled to Somalia in order to join the movement. It is important to note, however, that Al-Shabab maintains multiple tiers of media communication and messaging: (1) media aimed at transnational jihadis online, (2) Somali domestic and diaspora audiences via Somali language media outlets, which are as or more important than #1, (3) communications aimed at external enemies, for example via the “HSM Press” Twitter account and some of Al-Kata’ib’s videos.

On the operational front, AQC operatives in East Africa played a key role in training and providing ideological guidance to Al-Shabab in its formative days, though their exact roles remain hazy. Chief among these operatives were Abu Talha al-Sudani (killed in 2007 or 2008), Saleh ‘Ali Saleh al-Nabhani (killed in a U.S. military strike in southern Somalia on September 14, 2009), and Fazul ‘Abdullah Muhammad, also known as Fadil Harun (killed in a chance encounter in June 2001 at a Transitional Federal Government checkpoint in Mogadishu). Of the three, al-Nabhani occupied the most visible role in aiding Al-Shabab, appearing in a 24-minute video released by Al-Shabab’s media department in August 2008 in which he called on Muslims outside of Somalia to come and aid “their brothers” in that country. He made specific calls to Muslims in Sudan and Yemen, saying that “we are waiting for reinforcements from Sudan and Yemen, the places of wisdom (al-hikmah) and faith (al-iman).” Al-Nabhani is shown briefly instructing military exercises alongside Mukhtar Robow in the video. A day after al-Nabhani’s death, Al-Shabab issued a statement eulogizing him.

During a period of severe crisis in which it is dealing with the effects of a severe famine, declining diaspora financial and manpower support, and growing military pressures from AMISOM, the TFG, Ethiopia, Kenya, their allied militias, and the U.S., Al-Shabab may be wagering that by formally affiliating itself with AQC it will receive financial support or recruits that it may otherwise not have had access to. Questions remain, however, as to the timing of this announcement. AQC likely has little spare financial support or manpower that it can send to Al-Shabab, given the former’s needs in Afghanistan and Pakistan. If it was hoping for another safe haven in Somalia, AQC will likely be disappointed in Somalia since the “golden age” of Al-Shabab’s insurgent state is likely over. However, it may not be direct AQC support that Al-Shabab is aiming for but rather support from non-Somali jihadis who are sympathetic to AQC’s ideological message who may choose Somalia as their field of “jihad” and thus provide the insurgent movement with badly needed reinforcements.

On the operational level, it is unclear whether AQC still has key operatives in East Africa. The group’s original core group of operatives has died or been killed, likely leaving a vacuum that will be difficult for AQC to fill, particularly given its weakened state and need for all the financial and manpower resources it can get for the Afghanistan-Pakistan front. The only suspected AQC operative that has been revealed publicly since the chance killing of Fazul ‘Abdullah Muhammad at a TFG checkpoint in Mogadishu on June 8 of last year, has been Abu ‘Abdullah al-Muhajir, who the FBI believes to be American citizen Jehad Serwan Mostafa. He was present at a major media event staged in October by Al-Shabab and AQC at the insurgent movement’s flagship refugee camp, Al-Yasir, in the Lower Shabelle region, which has since been closed. The masked al-Muhajir delivered humanitarian and other aid to Al-Yasir. On banners present at the event, the identities of “AQ” and Al-Shabab were kept distinct and separate. The aid was labeled as being from “AQ” but distributed in coordination with Al-Shabab. Al-Muhajir’s exact role in AQC, if any, have not yet been specified in any detail by the group, nor was the aid distribution discussed in any detail, at least yet, in AQC media releases. Without significant infrastructure in the form of skilled operatives in Somalia, it is unlikely that the official announcement of Al-Shabab’s affiliation with AQC will bring about any immediate significant changes on the ground for the insurgent movement. The official announcement of affiliation does, however, potentially provide AQC with a propaganda coup in that it is able to continue presenting itself as relevant and it could also provide a new cause for its supporters to unify around.

‘Ali Mahamoud Rage (left) with Abu ‘Abdullah al-Muhajir at Al-Yasir camp in Lower Shabelle in mid-October

‘Ali Mahamoud Rage (left) with Abu ‘Abdullah al-Muhajir at Al-Yasir camp in Lower Shabelle in mid-October

Al-Shabab is also likely to remain focused on the ongoing conflict inside Somalia, though it will also likely continue to carry out attacks in Kenya and other neighboring countries that either have soldiers inside the country or have sent soldiers to join the AMISOM force. Given the reportedly high numbers of non-Somali foreign fighters that have joined its ranks (numbers remain unclear), it is possible that as Al-Shabab becomes increasingly desperate it will attempt to carry out more attacks against countries that are militarily engaged in Somalia. Al-Shabab has already, it seems, solidified an operational relationship with militant elements within the Kenyan Muslim population and it is likely that Al-Shabab has already and will continue to attempt to form relationships with other Muslim militant groups in the Horn of Africa. It is important to note that, unlike other AQC affiliates with the exception of AQAP and Ansar al-Shari‘a in Yemen, Al-Shabab has a significant domestic population over which it rules, a constituency so to speak, though clearly not all of the people support the movement’s rule. Domestic politics and social relations will likely continue to play a major role, if not the most important role, in determining Al-Shabab’s trajectory.

Al-Shabab is a hybrid movement, part domestic insurgency and part jihadi movement with a transnational flare. It is a “glocal” militant movement that, while focused mainly on waging a domestic insurgency, has deliberately cultivated relations with AQC, AQAP, and the transnational jihadi current which they represent, in part due to real ideological affinity and in for strategic reasons, mainly to expand its limited base of potential recruits and supporters. Its desire and ability to move fully into the transnational arena, defined here as outside Somalia and the Horn of Africa, remains an open question. It is possible that the movement will be ultimately uninterested in or incapable of, like AQIM, of moving fully into transnational militancy. Al-Shabab, despite facing major setbacks during the past year, has succeeded in establishing clandestine recruiting networks on several continents, developed a sophisticated set of media operations, and continues to prove that it remains a potent force inside Somalia, though how long it can remain so under increasing military pressure is unclear.

The possibility of fractures emerging in the movement, particularly as pressure mounts, remain perhaps the greatest danger to Al-Shabab’s existence as a unified, or fairly unified, militant force inside the country. These fractures will perhaps emerge following the formal affiliation of Al-Shabab with AQC, if consistent reports of a rift between Godane and more Somalia-centric Al-Shabab leaders are true. These fractures, however, may not emerge in the short term, as the insurgent movement has proven remarkably resilient in the fact of major crises such as the famine. The Al-Shabab media reaction, in the form of its own press statements, videos, and other media releases, to the official announcement of affiliation will also be telling with regard to how the insurgent movement itself, and not AQC, presents the affiliation. It also remains to be seen whether the distribution network of Al-Shabab media materials online changes, moving from the Sada al-Jihad (Echo of Jihad) Media Center of the Global Islamic Media Front (GIMF) to the Al-Fajr (The Dawn) Media Center, which distributes AQC, AQAP, ISI, and AQIM media materials exclusively, in addition to some of its own material. Even close allies of AQC in other regions, such as the Tehrik-i Taliban Pakistan and Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, do not have their media materials distributed via Al-Fajr. Such a shift would be a further sign of Al-Shabab’s full adoption into the AQ family.

As the idiom says, “watch this space.”